If you have nothing to die for, then you are not really living.

Martin Luther King

The prevailing belief among slaves at the time seemed to be that one needed no more than a “calling” from God to be considered a preacher. That was the norm Nat Turner grew up with, and that’s the way he became a preacher. He grew up experiencing visions, and feeling different, and even being treated differently than the other children around him. That is one reason he was considered a prophet.

In the Bible, the function of a prophet was to communicate God’s will to man. Often times, he was deemed as the spokesperson or the mouth by which God chose to speak to his people. Not only was he God’s instrument, he was also assigned the task of correcting moral and religious abuses. In essence, a prophet was looked upon to proclaim moral and religious truths. This is how I view Nat Turner’s rebellion, as a divine mission. He believed that he had been chosen by God to lead his people put of the oppressive situation they had been forced into by unjust circumstances beyond their control.

If one examines the Bible, he will find that much of the text deals with the oppressed and the oppressors. In the context of slavery, the reader must note that Christianity had distinct meanings for blacks and whites. For blacks, the Christian gospel provided hope, comfort, love and freedom from their oppression. For whites, the Christian gospel served as a tool to pacify the slaves and brainwash them into believing that it was God’s will to obey their masters.

Given this context, it is easy to understand the majority of slaves believed in God and the ideals of Christianity. After all, what higher authority is there than God’s word and his promise to free his believers. Thus, many slaves clung to the word of God because it would be their vehicle to escape oppression and be liberated. Even if it meant waiting until after their earthly lives were over.

Conversion to Christianity did more for the slave than to simply make him or her docile. It served to give the slave a fIxed point of reference in a world filled with uncertainty, contradiction, and crisis. Conversion involved the discovery by the slaves that God was not remote and unconcerned, but at their side in all the sufferings of daily life. Josiah I Henson recalled a sermon on a text from Hebrews which told of Christ having tasted death "for every man." "0 the blessedness and sweetness of feeling that I was LOVED," he exclaimed. This was in sharp contrast to the brutality he experienced daily from his master. (7)

Antebellum Christians felt that to be properly converted one must have a dramatic conviction of one's sin and be "born again." Not surprisingly, as slaves were converted they also told how they were seized by the Spirit, struck dead as it were, and raised to new life. Conversion could take place in a field, in the woods, at a camp meeting, in the slave quarters or a service conducted by the blacks themselves.

Many slaves had dramatic conversion experiences. John Jasper, a famous Negro preacher in antebellum Richmond, was converted while at work as a stemmer in a tobacco factory. Before this event Jasper felt as if he were in the pit of despair and his sins as large as mountains. But after a confrontation with the Spirit, slaves like Jasper felt like new men and women. A black revival preacher by the name of Pompey was so amazed by the change that came over him, that he doubted he was the same person. Then "he looked at his hands and felt of his wool, and found it was Pompey's skin and Pompey's wool but it was Pompey with a new heart." (8)

Interestingly, the life of the slave was sometimes made more miserable because he or she professed to be a Christian or sought to practice their religion. Unwilling to recognize blacks as their spiritual equals, there were some Whites who put pressure on their slaves to surrender the faith. An ex-slave from Virginia recalled how some Southerners would rather have the Negro fiddling and dancing than praying and preaching. (9)

A slave who wished to be baptized needed his master's permission and might be whipped if he failed to obtain it. Planters were known to violate the Christian principles of pious slaves by forcing them to work on the Sabbath and encouraging old vices. Slaves were constantly forced to choose between duty and religion. As one slave put it, "a slave cannot pray right, when, while on his knees, he hears his Master, 'here John'-- and he must leave his God and go to his Master." (10) Others viewed Christian morality as good for their slaves, but not for themselves. Harriet Jacobs told the story of a  slaveholder by the name of Litch who had a very peculiar notion of what "Thou shalt not steal" meant: "On his own plantation he required very strict obedience to the eighth commandment. But depredations on the neighbors were allowable, provided the culprit managed to evade detection or suspicion. (11) The hypocrisy of the situation was not lost on the slaves. The words of an old Negro spiritual sum it up this way :

slaveholder by the name of Litch who had a very peculiar notion of what "Thou shalt not steal" meant: "On his own plantation he required very strict obedience to the eighth commandment. But depredations on the neighbors were allowable, provided the culprit managed to evade detection or suspicion. (11) The hypocrisy of the situation was not lost on the slaves. The words of an old Negro spiritual sum it up this way :

We raise de wheat, Dey gib us de corn;

We bake de bread, De gib us de crust;

We sif de meal, Dey gib us de huss;

We peal de meat, Dey gib us de skin;

And dat's de way Dey take us in;

"We skim de pot, Dey gib us de liguor,

And say dat's good enough for nigger."

In order to survive, in order to keep body and soul together, the slaves often had to resort to behavior which was by strict accounting, in violation of the customary standard of Christian morality. Theft and deception, for example, were violations of not only the police law of the South but also in the eyes of the planters, the ethics of Christianity. Which of course, is in direct contradiction with their notions of slavery – the acceptance of the idea of people being stolen from their native lands and sold to other people as property, devoid of their rights and most basic humanity and dignity.

Some slave traders and owners asked more for Christian slaves, assuming them to be more faithful and trustworthy. The truth of the matter was that many slaves were able to justify theft and deception by an appeal to a higher morality than that prescribed for them by slaveholding piety. Nat Turner ascribed to this belief when he would go from plantation to plantation preaching in the slave cabins, all the while creating a map of the plantations to eventually be used in his rebellion.

Many slaves found freedom and hope in the prayer meetings they attended when a traveling preacher, such as Nat Turner, visited. These meetings, generally held inside slave cabins, or in the woods away from prying plantation eyes, were often referred to as “stealing away to Jesus”. Turner's prophetism made him a popular leader. He was able to use that which he knew the slaves would cleave to. He strategically appealed to their desire for inspiration, hope and belief in visions. Turner was then able to use religion and his visions as a catalyst for social disturbance. Even though Black evangelicalism shared much in common with its White counterpart, when the slaves held their own services, they added their own flourishes and unique styles to the White religious legacy. In so doing, they created an "invisible institution," a church that was their own.

Blacks also bequeathed something back to the evangelical tradition they borrowed from. The call and response pattern appears to be derived from the African heritage. There is fair body of evidence that suggests some Whites copied certain practices of Black worshippers. Shouting in worship, for example, is one such borrowing. Many blacks looked down on Whites who shouted in worship being poor copies of themselves, or in today’s parlance; "wanna- be's.”

Slaves that could get advantage of their owners through deception or trickery felt they had a perfect right to do so. When James Pennington was captured during an escape attempt, he told his captors that he had hid out with slaves who had small pox. When they dispersed to avoid contagion, he escaped once more. (12) Often slaves had to resort to petty theft as a means of supplementing their meager diet. One slave caught stealing from his master's corncrib was as "punctilious as a Pharisee" in his Sabbath observance, but had no qualms about taking the corn. He told his master, "Nigger take wat nigger raises." (13)

Another who was found guilty of stealing his master's meat from the smokehouse, said he was simply moving it from "out of one tub and putting it in another. The ownership of the meat was not affected by the transaction. At first he owned it in the tub, and last he owned it in me." (14) Booker T. Washington's mother was forced to steal eggs to feed her family. "Perhaps by some code of ethics," Washington wrote, this would be classed as stealing, but deep down in my heart I can never decide that my mother, under such circumstances was guilty of theft.” (15)

As these examples make clear, slaves worked out a contextual ethic in the demands of day to day living. They were not willing to be duped by a sham Christian piety which was mandatory for slaves but not for the masters. "When a man has his wages stolen from him year after year," one wrote, "and the laws sanction and enforce the theft, how can he be expected to have more regard to honesty than the man who robs him." We would be in error, however, if we assumed that when the Christian slave had to resort to theft or deception, he did so without a sense of the moral issues involved. (16)

Slavery was brutalizing in its effect on blacks, but it did not destroy the Christian slave's basic sense of right and wrong. James Pennington, the slave I mentioned a moment ago who lied to escape his captors, spoke of his "intense horror at a system which can put a man not only in peril of liberty, limb and life itself, but which can even send him in haste to the bar of God with a lie on his lips." Slaves did not think it right to steal from one another. Those who did so were called as "mean as master" or "just as mean as white folks." (17)

The complaint made by Whites that the Black slaves had no understanding of the Christian ethic cannot be sustained. Southerners were judging the slaves according to a standard of piety which protected the interests of the master but denied justice and mercy for the slave. The slaves acted according to a standard of piety which was based on principles of the true Gospel as they understood it. When the two came into conflict, the slave appealed to a higher law. If a neighbor brought a charge of theft against any of his slaves, he was browbeaten by the master who assured him that his slaves had enough of everything at home, and had no inducement to steal. No sooner was the neighbor's back turned than the accused was sought out, and whipped for lack of discretion.

The Reverend John Long honestly admitted his frustration in preaching to the slaves. They could not but be suspicious of the Christian gospel, he felt, when they daily observed whites who were assumably Christian violating its basic tenets. He was surprised that many of the slaves did not become "secret infidels." (18) Indeed, Black criticism of the hypocrisy of Southern White religion is a prominent theme in many slave narratives. (19) Slaves were able to judge inconsistency of conduct by holding up the performance of their masters and mistresses against the mirror of common humanity and the Christian gospel. They especially condemned the Whites who prayed with them on Sunday and beat them on Monday.

Slaves were also critical of the kind of White preaching which was obviously motivated by a desire to keep them in their place rather than offer them the freedom of the Gospel. Daniel Payne told a group of Lutherans in 1839 that he had often seen Negroes in the South scoff at the slaveholding White clergy while they were preaching, saying, "you had better go home and set your slaves free." (20)

He had often witnessed house servants sneering and laughing among themselves when summoned to family prayers by their mistress for they knew she would only read, "Servants obey your masters," and not "break every yoke and let the oppressed go free." Slaves were able to distinguish between the truths of the Word, and the professed practice of their masters." Most were certain they were closer to God than most Whites. (21)

Nat Turner believed this fervently. He knew he was different than those who he had grown up around, and most definitely different than the Whites who owned him. He didn’t indulge in the common vices many slaves around him did, preferring instead to spend his time praying and receiving visions. He had no doubt of his religious and moral superiority. He lived his beliefs everyday.

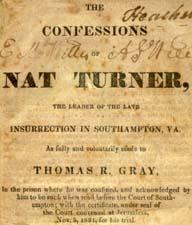

As I stated earlier, Nat Turner experienced many divine mystical visions throughout his life. He interpreted these visions to be the affirmation of his beliefs that God had chosen him for a singular purpose; to overthrow the current slave system so that the “first should be last and the last should be first.” Many of these visions can be interpreted as containing symbolic representations of the struggle against slavery. Although prophecy functioned to bring people closer to God, it was also used a to bring about change. Turner told of these visions while he was in prison after being captured when his revolt was over. I will include the excerpts of the relevant passages later, but want to discuss their possible meanings first.

Many prophets in the Bible were rebels who were able to manipulate the word of God to fit their political agenda and implement some form of revolution and social change. Nat Turner is no exception. Though his motivations are not clear, it is clear that he used his "ability" to reveal prophecy and interpret the Bible to win over followers who would support his insurrection.

Many prophets in the Bible were rebels who were able to manipulate the word of God to fit their political agenda and implement some form of revolution and social change. Nat Turner is no exception. Though his motivations are not clear, it is clear that he used his "ability" to reveal prophecy and interpret the Bible to win over followers who would support his insurrection.

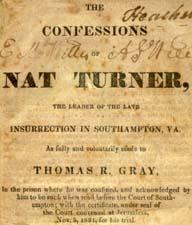

In the beginning of the confession, Turner describes he was destined to fulfill a great prophesy. He makes it a point to illustrate how others knew from his birth that he was someone special, extraordinary, and wonderful. "Others being called on were greatly astonished, knowing that these things had happened caused them to say in my hearing, I would surely be a prophet, as the Lord has shewn me things that had happened before my birth…I was intended for some great purpose.” (22)

I suggest that Turner believed his purpose was to apply the freeing power of the gospel to his enslaved brothers and sisters; perhaps he even used Biblical examples of groups that have been liberated such as the Israelites in Egypt and the Christians who were under Roman Rule. Turner was able to use Christianity and the gospel as inspiration to attempt to correct the social abuses of slavery. He took it upon himself to find ways in which he could use scripture to emancipate slaves from the mental, physical, and emotional bondage bestowed on them unjustly. Since the slaves looked to Christianity for inspiration and hope, it was only logical for Turner to draw followers through theology, appeasing to their feelings of defeat, hopelessness, and resentment toward whites for being stripped of their happiness and dignity; concepts that are promised to them in Scripture.

As the confession develops, one learns that Turner gains the confidence of his people. His superior judgment, thought to be Divinely inspired, is admired and deemed to be “perfect.” Not only does he have an elevated view of himself; his people do as well. One quickly understands that Turner is in a unique position to persuade and lead others since they to him with a degree of admiration and awe.

One also cannot overlook Turner’s constant references to his spiritual practices and frequent revelations from the Spirit. His describes in detail his daily prayer life and his fasting. I would argue that these references served to reassure the reader, the slaves, and Turner himself that the title of prophet bestowed upon him is well deserved.

It is clear throughout the confession that Turner is always cognoscent of his influence and potential impact on the minds of the slaves. "Knowing the influence I had obtained over the minds of my fellow servants, not by means of conjuring and such like tricks-for to them I always spoke of such things with contempt, but by the communion of the Spirit whose revelations I often communicated to them, and they believed and said my wisdom came from God.” (23)

The passage demonstrates that Turner knows that he can literally persuade his followers to believe anything he says because he is seen as a direct instrument of God. He becomes their messiah and hope for liberation. As the confession progresses and Turner discusses more revelations, he tells Gray that his dreams and visions were no longer his own, but rather God’s will manifesting itself through him. Turner believes these revelations are direct signs from the Holy Ghost.

To Turner, the discovery of blood drops on the corn is perhaps the most blatant and exact sign from God. He interprets it to mean that the Day of Judgment is rapidly approaching and that it is his duty to fight against the Serpent (slavery). The evil serpent is the whiteness that is holding the blacks captive and keeping them from receiving their promise of liberation. The blood is representative of the blood Christ shed on earth for his sinners so that they may be free. Turner expresses to Gray that the signs revealed that it was time for "the first to be last and the last to be first". (24) The Spirits would allow him to wait no longer.

The line "And on the appearance of the sign, (the eclipse of the sun last February) I should arise and prepare myself, and slay my enemies with their own weapons" (25) is very interesting because from this statement two conclusions can be drawn. Perhaps Turner is stating literally that he is going to slay his enemies with their weapons i.e. guns, axes, knives, etc.

But one may also interpret this idea to mean that he is referring to their "weapon" of Christianity which he believes has been used to keep the slaves oppressed. Ironically, he uses the same faith, God, and scripture that was meant to pacify the slaves in order to destroy the people who are enslaving them.

Some suggest that Turner may have profited by the role he played as leader of this insurrection, that his recurring visions might have been more "critical to his self-conception than to the effects or ideology of his revolt". (26) According to one source, Turner’s uprising should be categorized as a social movement; falling between pure millenarianism, which expects a revolution to be inspired by divine revelation and pure revolutionism, which develops out of a desire to overthrow an existing order.

The juxtaposition between religion and a revolution is evidenced in Turner’s revolution. "Marked by Christian messianism but at the same time by a fundamental vagueness and lack of clear purpose, such movements, in there want of an effective strategy, ‘push the logic of revolutionary position to the point of absurdity or paradox, becoming visionary, apocalyptic, and utopian.” (27)

It may be beneficial to note that in a biblical context, prophecy gave the oppressor or those who were not succumbing to God’s will a chance to change their ways before the wrath of God had to be implemented. One can make the same analogy with Nat Turner’s insurrection. If the slaves truly believed in the gospel, and I argue that most did, then they truly believed in its promise to deliver them out of their suffering.

To Turner, the white men had had the opportunity to yield to God’s will and lift the chains of oppression. However when this did not happen, Turner believed that it was time to take action. He sought to fulfill the prophecies that had been shown to him. Hence, the destruction of the slaveholders and their families was the only logical way to obtain freedom.

Like other "prophets", Turners revolution and charge to bring about social change included a great deal of violence. Clearly Turner is not opposed to bloodshed. Perhaps he believed that the only way to free his people was to resort to the type of treatment that had kept them enslaved. It can also be noted that Turner’s insurrection and prophecy was similar to certain prophets in the Old Testament. The Old Testament is has its fair share of fighting, war, and bloodshed. A prevalent mentality was "an eye for an eye". In essence, one may say that if the system of oppression is evil, then the use of violence to rid society of such an evil is justified and necessary.

Many argue that Turner used Christianity as a means of manipulation, drawing the masses together by an exterior commonality to achieve an inward goal. It seems that Turner truly believed that the white people were beyond redemption and that it was his "calling" to destroy it.

This religious ecstasy was seen as madness to the Southern press. They simply could not understand how a rebellion motivated by Christianity could advocate the killing of woman and children. One of the first accounts of the insurrection was published in The Richmond Compiler on August 24, 1831. Nat Turner and his rebels are seen as savages. "The wretches who have conceived this thing are mad-infatuated-deceived by some artful knaves, or stimulated by their own miscalculating passion." (28)

Turner’s prophetism was what made him a popular leader. He was able to use that which he knew the slaves would cleave to. He strategically appealed to their desire for inspiration, and told them of his divine visions. Turner was able use religion as a catalyst for social disturbance. Perhaps the most appropriate term for Turner’s insurrection is rebellion for this term implies destruction and discord. His prophetic mission to lead his people to freedom was to no avail. "Turner’s prophetism, however, exists as the pure expression of millenarian belief that the rising of American slaves would be the mechanism of God’s judgment.” (29)

And one can not argue the impact had on the mind-sets of both the White and Black residents of Southampton County. Many Whites became aware, seemingly for the first time, that their slaves were so unhappy that they were willing to risk certain death (if captured) and stage a revolt against the institution of slavery. Their misplaced complacency with the system had ended.

In my childhood a circumstance occurred which made an indelible impression on my mind, and laid the ground work of that enthusiasm, which has terminated so fatally to many both white and black, and for which I am about to atone at the gallows. It is here necessary to relate this circumstance -trifling as it may seem, it was the commencement of that belief which has grown with time, and even now, sir, in this dungeon, helpless and forsaken as I am, I cannot divest myself of it.

Being at play with other children, when three or four years old, I was telling them something, which my mother overhearing, said it had happened before I was born -I stuck to my story, however, and related some things which went in her opinion to confirm it -others being called on were greatly astonished, knowing that these things had happened, and caused them to say in my hearing, I surely would be a prophet, as the Lord had shewn me things that had happened before my birth.

And my father and mother strengthened me in this my first impression, saying in my presence, I was intended for some great purpose, which they had always thought from certain marks on my head and breast- (a pracel of excrescences which I believe are not at all uncommon, particularly among Negroes, as I have seen several with the same. In this case he has either cut them off, or they have nearly disappeared.)

My grandmother, who was very religious, and to whom I was much attached -my master, who belonged to the church, and other religious persons who visited the house, and whom I often saw at prayers noticing the singularity of my manners I suppose and my uncommon intelligence for a child, remarked I had too much sense to be raised – and if I was, I would never be of any service to anyone – as a slave – to a mind like mine, restless, inquisitive and observing of everything that was passing, it is easy to suppose that religion was the subject to which it was directed, and although this subject principally occupied my thoughts, there was nothing I saw or heard of to which my attention was not directed.

The manner in which I learned to read and write, not only had great influence on my own mind, as I acquired it with the most perfect ease, so much so, that I have no recollection whatever of learning the alphabet -but to the astonishment of the family, one day, when a book was shewn me to keep me from crying, I began spelling the names of different objects -this was a source of wonder to all in the neighborhood, particularly the blacks -and this learning was constantly improved at all opportunities.

When I got large enough to go to work, while employed, I was reflecting on many things that would present themselves to my imagination, and whenever an opportunity occurred of looking at a book, when the school children were getting their lessons, I would find many things that the fertility of my own imagination had depicted to me before; all my time, not devoted to my master's service, was spent either in prayer, or in making experiments in casting different things in moulds made of earth, in attempting to make paper, gunpowder, and many other experiments, that although I could not perfect, yet convinced me of its practicability if I had the means.

I was not addicted to stealing in my youth, nor have ever been -yet such was the confidence of the Negroes in the neighborhood, even at this early period of my life, in my superior judgment, that they would often carry me with them when they were going on any roguery, to plan for them growing up among them, with this confidence in my superior judgment, and when this, in their opinions, was perfected by Divine inspiration, from the circumstances already alluded to in my infancy, and which belief was ever afterwards zealously inculcated by the austerity of my life and manners, which became the subject of remark by white and black. Having soon discovered to be great, I must appear so, and therefore studiously avoided mixing in society, and wrapped myself in mystery, devoting my time to fasting and prayer.

I was not addicted to stealing in my youth, nor have ever been -yet such was the confidence of the Negroes in the neighborhood, even at this early period of my life, in my superior judgment, that they would often carry me with them when they were going on any roguery, to plan for them growing up among them, with this confidence in my superior judgment, and when this, in their opinions, was perfected by Divine inspiration, from the circumstances already alluded to in my infancy, and which belief was ever afterwards zealously inculcated by the austerity of my life and manners, which became the subject of remark by white and black. Having soon discovered to be great, I must appear so, and therefore studiously avoided mixing in society, and wrapped myself in mystery, devoting my time to fasting and prayer.

By this time, having arrived to man's estate, and hearing the Scriptures commented on at meetings, I was struck with that particular passage which says: "Seek ye the kingdom of Heaven and all things shall be added unto you." I reflected much on this passage, and prayed daily for light on this subject - As I was praying one day at my plough, the spirit spoke to me, saying, "Seek ye the kingdom of Heaven and all things shall be added unto you."

Question: What do you mean by the Spirit.

Answer: The Spirit that spoke to the prophets in former day - and I was greatly astonished, and for two years prayed continually, whenever my duty would permit - and then again I had the same revelation, which fully confirmed me in the impression that I was ordained for some great purpose in the hands of the Almighty.

Several years rolled round, in which many events occurred to strengthen me in this my belief. At this time I reverted in my mind to the remarks made of me in my childhood, and the things that had been shewn me - and as it had been said of me in my childhood by those by whom I had been taught to pray, both white and black, and in whom I had the greatest confidence, that I had too much sense to be raised, and if I was I would never be of any use to any one as a slave.

Now finding I had arrived to man's estate, and was a slave, and these revelations being made known to me, I began to direct my attention to this great object, to fulfil the purpose for which, by this time, I felt assured I was intended- Knowing the influence I had obtained over the minds of my fellow servants, (not by the means of conjuring and such like tricks - for to them I always spoke of such things with contempt) but by the communion of the Spirit whose revelations I often communicated to them, and they believed and said my wisdom came from God. I now began to prepare them for my purpose, by telling them something was about to happen that would terminate in fulfilling the great promise that had been made to me –

About this time I was placed under an overseer, from whom I ran away - and after remaining in the woods thirty days, I returned, to the astonishment of the negroes on the plantation, who thought I had made my escape to some other part of the country, as my father had done before. But the reason of my return was, that the Spirit appeared to me and said I had my wishes directed to the things of this world, and not to the kingdom of Heaven, and that I should return to the service of my earthly master -"For he who knoweth his Master's will, and doeth it not, shall be beaten with many stripes, and thus have I chastened you."

And the negroes found fault, and murmured against me, saying that if they had my sense they would not serve any master in the world. And about this time I had a vision - and I saw white spirits and black spirits engaged in battle, and the sun was darkened - the thunder rolled in the Heavens, and blood flowed in streams - and I heard a voice saying, "is your luck, such you are called to see, and let it come rough or smooth, you must surely bear it."

I now withdrew myself as much as my situation would permit, from the intercourse of my fellow servants, for the avowed purpose of serving the Spirit more fully - and it appeared to me, and reminded me of the things it had already shown me, and that it would then reveal to me the knowledge of the elements, the revolution of the planets, the operation of tides, and changes of the seasons.

After this revelation in the year 1825, and the knowledge of the elements being made known to me, I sought more than ever to obtain true holiness before the great day of judgment should appear, and then I began to receive the true knowledge of faith.

And from the first steps of righteousness until the last, was I made perfect; and the Holy Ghost was with me, and said "Behold me as I stand in the Heavens" - and I looked and saw the forms of men in different attitude - and there were lights in the sky to which the children of darkness gave other names than what they really were - for they were the lights of the Saviour's hands, stretched forth from east to west, even as they were extended on the cross on Calvary for the redemption of sinners.

And I wondered greatly at these miracles, and prayed to be informed of a certainty of the meaning thereof - and shortly afterwards, while labouring in the field, I discovered drops of blood on the corn, as though it were dew from heaven - and I communicated it to many, both white and black, in the neighbourhood - and I then found on the leaves in the woods hieroglyphic characters and numbers, with the forms of men in different attitudes, portrayed in blood, and representing the figures I had seen before in the heavens.

And now the Holy Ghost had revealed itself to me, and made plain the miracles it had shown me - For as the blood of Christ had been shed on this earth, and had ascended to heaven for the salvation of sinners, and was now returning to earth again in the form of dew - and as the leaves on the trees bore the impression of the figures I had seen in the heavens, it was plain to me that the Saviour was about to lay down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and the great day of judgement was at hand. –

About this time, I told these things to a white man, (Etheldred T. Brantley) on whom it had a wonderful effect - and he ceased from his wickedness, and was attacked immediately with a cutaneous eruption, and blood oozed from the pores of his skin, and after praying and fasting nine days, he was healed, and the Spirit appeared to me again, and said, as the Saviour had been baptised, so should we be also - and when the white people would not let us be baptised by the church, we went down into the water together, in the sight of many who reviled us, and were baptised by the Spirit

After this I rejoiced greatly, and gave thanks to God. And on the 12th of May, 1828, I heard a loud noise in the heavens, and the Spirit instantly appeared to me and said the Serpent was loosened, and Christ had laid down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and that I should take it on and fight against the Serpent, for the time was fast approaching, when the first should be last and the last should be first.

Question: Do you not find yourself mistaken now?

Answer: Was not Christ crucified? And by signs in the heavens that it would be made known to me when I should commence the great work- - and until the first sign appeared, I should conceal if from the knowledge of men- -And on the appearance of the sign (the eclipse of the sun last February), I should arise and prepare myself, and slay my enemies with their own weapons. And immediately on the sign appearing in the heavens, the seal was removed from my lips, and I communicated the great work laid out before me to do, to four in whom I had the greatest confidence (Henry, Hark, Nelson, and Sam)- -It was intended by us to have begun the work of death on the 4th of July last- -Many were the plans formed and rejected by us, and it affected my mind to such a degree, that I fell sick, and the time passed without our coming to any determination how to commence- -still forming new schemes and rejecting them, when the sign appeared again, which determined me not to wait longer.

Since the commencement of 1830, I had been living with Mr. Joseph Travis, who was to me a kind master, and placed the greatest confidence in me: in fact, I had no cause to complain of his  treatment of me. On Saturday evening, the 20th of August, it was agreed between Henry, Hark, and myself, to prepare a dinner the next day for the men we expected, and then to concert a plan, as we had not yet determined on any. Hark, on the following morning, brought a pig, and Henry brandy, and being joined by Sam, Nelson, Will and Jack, they prepared in the woods a dinner, where, about three o'clock, I joined them.

treatment of me. On Saturday evening, the 20th of August, it was agreed between Henry, Hark, and myself, to prepare a dinner the next day for the men we expected, and then to concert a plan, as we had not yet determined on any. Hark, on the following morning, brought a pig, and Henry brandy, and being joined by Sam, Nelson, Will and Jack, they prepared in the woods a dinner, where, about three o'clock, I joined them.

Question: Why were you so backward in joining them?

Answer: The same reason that had caused me not to mix with them for years before. I saluted them on coming up, and asked Will how came he there, he answered, his life was worth no more than others, and his liberty as dear to him. I asked him if he thought to obtain it? He said he would, or lose his life. This was enough to put him in full confidence.

Jack, I knew, was only a tool in the hands of Hark, it was quickly agreed we should commence at home (Mr. J. Travis') on that night, and until we had armed and equipped ourselves, and gathered sufficient force, neither age nor sex was to be spared (which was invariably adhered to). We remained at the feast, until about two hours in the night, when we went to the house and found Austin; they all went to the cider press and drank, except myself.

On returning to the house Hark went to the door with an axe, for the purpose of breaking it open, as we knew we were strong enough to murder the family, if they were awakened by the noise; but reflecting that it might create an alarm in the neighborhood, we determined to enter the house secretly, and murder them whilst sleeping. Hark got a ladder and set it against the chimney, on which I ascended, and hoisting a window, entered and came down stairs, unbarred the door, and removed the guns from their places. It was then observed that I must spill the first blood.” (31)

(Nat Turner then goes on to talk about the rebellion, the separation from his men and six-week timeframe when he was pursued. I omitted these passages, and pick up the confessions at their end.) “During the time I was pursued, "had many hair breadth escapes, which your time will not permit you to relate. I am here loaded with chains, and willing to suffer the fate that awaits me.

Mr. Gray: I here proceeded to make some inquiries of him, after assuring him of that certain death that awaited him, and that concealing anything from me would only brIng destruction on the innocent as well as guilty, of his own color, If he knew of any extensive or concerted plan. His answer was, I do not. When I questioned him as to the insurrection in North Carolina happening about the same time, he denied any knowledge of it; and when I looked him in the face as though I would search his inmost thoughts, he replied, "I see sir, you doubt my word; but can you not think the same ideas, and strange appearances about this time in the heavens might prompt others, as well as myself, to this undertaking."

I now had much conversation with and asked him many questions, having forborne to do so previously, except in the cases noted in parentheses; but during his statement, I had, unnoticed by him, taken notes as to some particular circumstances, and having the advantage of his statement before me in writing, on the evening of the third day that I had been with him, I began a cross examination, and found his statement corroborated by every circumstance coming within my own knowledge, or the confessions of others whom had been either killed or executed, and whom he had not seen or had any knowledge since 22nd of August last, he expressed himself fully satisfied as to the impracticability of his attempt.

It has been said he was ignorant and cowardly, and that his object was to murder and rob for the purpose of obtaining money to make his escape. It is notorious, that he was never known to have a dollar in his life; to swear an oath, or drink a drop of spirits. As to his ignorance, he certainly never had the advantages of education, but he can read and write (it was taught him by his parents), and for natural intelligence and quickness of apprehension, is surpassed by few men I have ever seen.

As to his being a coward, his reason as given for not resisting Mr. Phipps, shews the decision of his character. When he saw Mr. Phipps present his gun, he said he knew it was impossible for him to escape, as the woods were full of men; he therefore thought it was better to surrender, and trust to fortune for his escape. He is a complete fanatic, or plays his part most admirably. On other subjects he possesses an uncommon share of intelligence, with a mind capable of attaining any thing; but warped and perverted by the influence of early impressions.

He is below the ordinary stature, though strong and active, having the true Negro face, every feature of which is strongly marked. I shall not attempt to describe the effect of his narrative, as told and commented on by himself, in the condemned hole of the prison. The calm, deliberate composure with which he spoke of his late deeds and intentions, the expression of his fiend-like face when excited by enthusiasm, still bearing the stains of the blood of helpless innocence about him; clothed with rags and covered with chains; yet daring to raise his manacled hands to heaven, with a spirit soaring above the attributes of man; I looked on him and my blood curdled in my veins.

I will not shock the feelings of humanity, nor wound afresh the bosoms of the disconsolate sufferers in this unparalleled and inhuman massacre, by detailing the deeds of their fiend-like barbarity. There were two or three who were in the power of these wretches, had they known it, and who escaped in the most providential manner.

The court composed of ---, having met for the trial of Nat Turner, the prisoner was brought in and arraigned, and upon his arraignment pleaded Not guilty; saying to his counsel, that he did not feel so. On the part of the Commonwealth, Levi Waller was introduced, who being sworn, deposed as follows: (agreeably to Nat's own Confession.) Col. Trezvant [2] was then introduced, who being sworn, numerated Nat's Confession to him, as follows: (His Confession as given to Mr. Gray.) The prisoner introduced no evidence, and the case was submitted without argument to the court, who having found him guilty, Jeremiah Cobb, Esq. Chairman, pronounced the sentence of the court, in the following words: "Nat Turner! Stand up. Have you any thing to say why sentence of death should not be pronounced against you?"

Answer. I have not. I have made a full confession to Mr. Gray, and I have nothing more to say. "Attend then to the sentence of the Court. You have been arraigned and tried before this court, and convicted of one of the highest crimes in our criminal code. You have been convicted of plotting in cold blood, the indiscriminate destruction of men, of helpless women, and of infant children. The evidence before us leaves not a shadow of doubt, but that your hands were often imbrued in the blood of the innocent; and your own confession tells us that they were stained with the blood of a master; in your own language, "too indulgent." Could I stop here, your crime would be sufficiently aggravated. But the original contriver of a plan, deep and deadly, one that never can be effected, you managed so far to put it into execution, as to deprive us of many of our most valuable citizens; and this was done when they were asleep, and defenceless; under circumstances shocking to humanity.

And while upon this part of the subject, I cannot but call your attention to the poor misguided wretches who have gone before you. They are not few in number -they were your bosom associates; and the blood of all cries aloud, and calls upon you, as the author of their misfortune. Yes! You forced them unprepared, from Time to Eternity. Borne down by this load of guilt, your only justification is, that you were led away by fanaticism. If this be true, from my soul I pity you; and while you have my sympathies, I am, nevertheless called upon to pass the sentence of the court. The time between this and your execution, will necessarily be very short; and your only hope must be in another world. The judgment of the court is, that you be taken hence to the jail from whence you came, thence to the place of execution, and on Friday next, between the hours of 10 A.M. and 2 P.M. be hung by the neck until you are dead! dead! dead! and may the Lord have mercy upon your soul."

A list of persons murdered in the Insurrection, on the 21st and 22nd of August, 1831: Joseph Travers and wife and three children, Mrs. Elizabeth Turner, Hartwell Prebles, Sarah Newsome, Mrs. P. Reese and son William, Trajan Doyle, Henry Bryant and wife and child, and wife's mother, Mrs. Catherine Whitehead, son Richard and four daughters and grandchild, Salathiel Francis, Nathaniel Francis' overseer and two children, John T. Barrow, George Vaughan, Mrs. Levi Waller and ten children, William Williams, wife and two boys, Mrs. Caswell Worrell and child, Mrs. Rebecca Vaughan, Ann Eliza Vaughan, and son Arthur, Mrs. John K. Williams and child, Mrs. Jacob Williams and three children, and Edwin Drury - - amounting to fifty-five. (32)

What is fascinating to note is Mr. Gray’s assessment of Nat Turner. Since he was a product of his times one should not be surprised that he is amazed by Nat Turner’s education and eloquence, and additionally his convictions. When trying to trip Nat up with words of his own “confession” uttered and transcribed days before, Gray finds that there are no discrepancies. A faithful reader would argue that of course there weren’t, for Nat was an instrument of God.

The Turner rebellion did not occur in a vacuum. During this time a conflict had developed in the North between theological conservatives who wished to maintain traditional Calvinist doctrine of unqualified human depravity and moderates who had a somewhat more optimistic view of human nature. Throughout the 19th century religious debate over slavery there was, generally speaking, a correlation between beliefs about human nature and attitudes toward race relations. The closer people adhered to the “Christian doctrine of human nature” which emphasized human sinfulness and powerlessness to do good, the more likely they were to support slavery as an institution.

And the more optimistic (a traditionalist theologian perhaps would say naïve belief) that people were about human nature the more likely they were to want to abolish slavery. One could also argue that a more literal interpretation of the Bible would strongly suggest that the slave owners could not call themselves Christians, as they were in no way mirroring Christ’s behavior in the treatment of their fellow man, missing the first tenet that the slaves were indeed “their fellow man.”

The slaves, it must be said, were not blind to the existence of pious white Christians who did the best they could to live up to the demands of their faith. Slaves seemed to have developed a deep feeling of gratitude toward those plantation missionaries who braved the rigors of climate and travel to minister to them. Many slaves gladly went to hear the gospel preached. The sermons were simple, and they understood them. Moreover, it was the first time many had ever been addressed as human beings. One group of slaves collected $45 to buy a suit for their preacher. One minister related that during his first year the blacks in his care would see him coming and say, "Yonder comes the preacher;" the second year, "our preacher;" and the third, "my preacher." (33)

So when on a Southampton County, VA, farm in 1831, preacher and prophet Nat Turner, organized a small band of men (his disciples) to help carry out what he considered to be the will of God, he had no qualms about their divine mission. The culmination of this act was the most destructive slave insurrection in U.S. history. This rebellion was not the first act of organized violent resistance to slavery in the United States, nor was it the last. It was, however, the most significant early example of organized black religious nationalism in the country.

So when on a Southampton County, VA, farm in 1831, preacher and prophet Nat Turner, organized a small band of men (his disciples) to help carry out what he considered to be the will of God, he had no qualms about their divine mission. The culmination of this act was the most destructive slave insurrection in U.S. history. This rebellion was not the first act of organized violent resistance to slavery in the United States, nor was it the last. It was, however, the most significant early example of organized black religious nationalism in the country.

Using religion as the primary tool to galvanize the masses, Prophet Nat, as he was called by local blacks, attempted to secure liberation by the violent destruction of the Peculiar Institution, as slavery was called by Turner and others. Attempting to accomplish what they deigned as their divine duty, the insurgents killed between fifty-three and sixty-one while people in the area, sparing only a few White lives, including a desperately poor family who owned no slaves and lived a life that was under wretchedly impoverished conditions.

The Nat Turner insurrection demonstrated that the religion of the white planter, modified to accommodate the liberation-oriented Turner and the enslaved populace of the area, was the ideological cornerstone of the uprising and the driving force of rebellion. Webster’s Dictionary defines insurrection as “rising up against an established authority, rebellion or revolt”. Nat Turner was leading an insurrection in the purest sense.

Notwithstanding the exigencies of slavery, the spirit of resistance found a comfortable niche in the dogma of Christianity and propelled a handful of people to develop immediately into a group of nearly sixty. Nat Turner, like black Christian nationalist leaders who would succeed him in the next century, accepted Christianity as a philosophical vehicle of liberation and resistance. Turner did not accept the "plantationized" notion of Christianity, which implored slaves to embrace docility and obey their masters in hope of being slaves in Heaven.

Christianity, as the religious center of the spiritual world for most enslaved Africans, and modified by Prophet Nat, became the antithesis of the religious tool of oppression and submission promoted by enslavers. Spawned from the revolt was the palpable white fear of independent black religious leadership, reflecting white people’s consternation over the potential of autonomous black ministers. Turner’s rebellion raised southern fears of a general slave uprising and had a profound influence on the attitude of Southerners towards slavery. Since the 1790's when slaves rebelled in Santo Domingo and slaughtered 60,000 people, Southerners realized that their own slaves might rise up against them. A number of slave revolt conspiracies were uncovered in the South between 1820 and 1831 but none frightened Southerners as much as Nat Turner's rebellion.

Perhaps the thing that the Southerners feared most was the religious Black nationalism that Nat Turner espoused and embodied. Most Whites of the time preferred to think of the Black slaves in a childlike manner who needed their constant guidance and oversight. Black nationalism is simply defined as the belief that Black people, acting independently of Whites, should create viable Black institutions for their survival. Otherwise, liberation cannot be realized for the masses of Black people. Racial pride, dignity, racial separation and hard work are the staples of Black nationalism. The operating definition of religious nationalism is the belief that black people are the center of their own spiritual universe. God speaks to them as His chosen ones and leads them toward liberation by the creation of a spiritual – if not physical-black nation. Nat Turner believed he had received divine visions and courageously acted upon them in an attempt to free his people.

Though Nat Turner’s revolt ultimately ended in defeat, it had had a huge impact. Millions could see that slaves were not in fact, content in bondage – but were straining against the most brutal conditions. It also continued to feed the idea of slave revolt and the need for the abolition of slavery. White reaction to Nat Turner's slave rebellion of 1830 influenced policy that shaped the free blacks' position in Richmond for the remainder of the Antebellum period. Like earlier rebellions, Nat Turner's Rebellion brought a rash of reactionary policy from the white Virginia lawmakers. Concurrent with the rebellion was the rise of abolitionist movement. This liberal movement originated in the Northeast but spread throughout the country through literature. Both the rebellion and the abolitionist movement caused the passage of reactionary laws that restricted the freedom of free blacks. (34)

In 1831-1832, the Virginia State Legislature enacted a series of these laws that directly affected the free black citizens of Richmond. A law was passed which prohibited the teaching of Negroes to read or write. This law was a direct response to the influx of abolitionist literature circulating the South. Another law banned Negro preaching. Finally, to curb the potential of any future Negro uprisings, a law was passed in 1832 that prohibited Negroes from possessing firearms. (35)

In court, Nat Turner pled "Not guilty" - saying he felt no guilt. On November 5, he was convicted of insurrection. On November 11, he walked to the hanging tree without any signs of fear, refused to speak last words, and was executed. After he was killed, his body was cut up skinned by his oppressors. The heirs of his owner were given $375 after his execution - apparently what the slave state of Virginia thought this heroic leader was worth. (36) No wonder the slaves sang, ‘Ole Satan's church is here below; up to God's free church I hope to go.

Historically, all reactionary forces on the verge of extinction invariably

conduct a last desperate struggle against the revolutionary forces.

Mao Tsetung, the Red Book

Footnotes

1.) Webster’s New World Dictionary, 3rd College Edition, Webster’s New World, NY, 1988

2.) Nat Turner, Confessions of Nat Turner, Eric Foner, ed. Prentice Hall, NJ, 1971

3.) Ibid.

4.) Ibid.

5.) Ibid.

6.) Ibid.

7.) Kenneth Greenberg, The Confessions of Nat Turner and Related Documents, St. Martin’s Press, NY, 1996

8.) Ibid.

9.) Ibid.

10.) Ibid.

11.) Ibid.

12.) Ibid.

13.) JC Inscoe, Slave Rebellion in the First Person: The Literary Quotes & Confessions of Nat Turner & Dessa Rose, article, Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 97, No. 4, October, 1989

14.) Ibid.

15.) Ibid.

16.) Ibid.

17.) Ibid.

18.) Ibid.

19.) Lawrence Levine, African Culture and Slavery in the United States,

Global Dimensions

20.) Ibid.

21.) Ibid.

22.) Nat Turner, Confessions of Nat Turner, Eric Foner, ed. Prentice Hall, NJ, 1971

23.) Ibid.

24.) Ibid.

25.) Ibid.

26.) Stephen B. Oates, The Fires of Jubilee: Nat Tuner’s Fierce Rebellion, Harper & Row, NY, 1975

27.) Ibid.

28.) H. Tragle, The Richmond Virginia Compiler, August 24, 1831. The Southampton Slave Revolt of 1831: A compilation of Source Material, Amherst, MA, University of Massachusetts Press, 1971

29.) Ibid.

30.) Terry Bisson, Nat Turner, Slave Revolt Leader, Chelsea House Press, NY 1988

31.) Nat Turner, Confessions of Nat Turner, Eric Foner, ed., Prentice Hall, NJ, 1971

32.) Ibid.

33.) Joseph R. Washington, jr. Race & Religion in Early 19th Century America, 1800-1850, Constitution, Conscience & Calvinist Compromise, Edwin Mellen Press, NY, 1988

34.) Ibid.

35.) Ibid.

36.) Stephen B. Oates, The Fires of Jubilee: Nat Tuner’s Fierce Rebellion, Harper & Row, NY, 1975